Spreads: The building blocks of options trading

Multiple-option strategies: How to spread

If you’re reading this, you probably know a thing or two about single options strategies like buying calls and puts. It makes sense that you started there since they’re the most commonly traded option strategies. They’re more straightforward, relatively cheap, and usually the easiest strategy to understand. Buying calls and puts are pure plays on the direction of the underlying stock. For many options traders, the journey ends there, and that’s ok.

But for others, there’s an entire world of possibilities to explore with options. Do you wish you could take a directional position without buying options premium, and thus put time decay in your favor? Maybe you think volatility is high relative to its historical average and you want to sell it. What if your charting skills have identified an area where the stock might move sideways and you’re looking to profit from a sideways market? Or perhaps you want to buy a call or put but you wish it wasn’t so expensive. This is where spreads come in.

What’s a spread?

A spread is a combination of two or more different options that include both long and short positions, or “legs.” Spreads can be bought for a debit or sold for a credit. They are generally risk-defined, and can be created and combined in various arrangements. Think of spreads like Legos. You can piece them together in different shapes and sizes to build something unique. Each option in the spread has a job, and together, the goal is to profit, as a package.

They’re called “spreads'' because the options in each strategy can be spread across price, time, or volatility, or all three through various combinations of long and/or short options, different strike prices, and the same (or even different) expiration periods. Which is just a long-winded way of saying spreads allow you a level of versatility, strategy, and in many ways, let you be creative.

The most common spreads which we’ll discuss in this article are debit spreads, credit spreads, and iron condors. They all have the same expiration date, and each will contain a combination of both long and short options.

The strategies

The most basic three spreads are usually the most commonly used—debit spreads, credit spreads, and iron condors (we promise, this is a strategy, not a comic book character), and are worth knowing since they serve as the building blocks of many other spreads. While debit and credit spreads are for speculating on direction (up or down), iron condors are for speculating on direction-less markets that are moving sideways.

First up: Debit spreads (aka long vertical spreads)

If you’re bullish or bearish on a stock, but buying calls and puts gets too expensive, a debit spread can help. To build a debit spread (call or put) start with a long option and add in a short option that’s further out of the money.

Bullish debit spreads use calls while bearish debit spreads use puts, and options are traded on a 1:1 ratio in the same expiration. Together, the net price of the two options equals the total cost of the spread. The max value a spread can reach is the difference between the strikes. This spread can still profit if the stock moves the right direction, but it’s more insulated from an implied volatility (aka “IV”) drop than just a long option by itself.

Let’s look at these two spreads in detail:

CALL DEBIT SPREAD (other names: long call spread or long call vertical)

PROFIT GRAPH:

WHY TRADE IT? You think a stock is going up within a certain time frame

OPTIMAL CONDITIONS: Low implied volatility, bullish stock, sector, and market

SETUP: Long Call + short higher strike call in the same expiration

EXAMPLE: Buy August 50 Call for $5 and sell Aug 55 Call for $2. Net cost = $3 (x100 = $300 per spread)

COST: Cost of long call, less premium received for short call (In this example, $3)

THEORETICAL MAX PROFIT: Limited to distance between strikes minus cost of trade ($5 wide spread - $3 net cost = $2 max profit)

THEORETICAL MAX LOSS: Net cost (debit) of trade (In this example, $3)

BREAKEVEN AT EXPIRATION: There’s one breakeven point (at expiration) at the long strike plus the debit paid (50 +$3 = $53 breakeven)

BEST CASE TO NAIL IT: Stock moves higher immediately, resulting in a profit. A simultaneous rise in implied volatility could help, too, but the rise in the short option would somewhat offset the rise in the long option.

WHAT CAN GO WRONG? Stock doesn’t rise quickly enough, or the stock is below the breakeven point as expiration nears.

A drop in implied volatility and time decay could deflate the option premiums while the trade is on. The long option will likely drop in value. However, since there is a short option that benefits from the deflating value, the impact overall is less than if it were just a long call position.

CLOSING THE TRADE: Just like buying single options, your goal is to buy a call debit spread and sell it for a higher price in order to profit, ideally as a package. The optimal way to do this is to simply execute the opposite transaction –sell the lower call strike and buy the higher call strike, as a package, for a credit.

If the stock goes above both strikes (keep in mind, this is the best-case scenario), you’ll be near the max theoretical profit. You might consider closing the trade before expiration to lock in profits. This could mean selling the spread at slightly less than max value in order to eliminate any downside risk before expiration.

If the position has moved against you, consider setting a price where you will sell the spread to cut your losses and close your position. If there is no bid (0 bid means there’s no willing buyer) for the spread at expiration, simply let both legs expire worthless and they will be removed from your account after expiration. If this happens, the loss will be limited to the net debit paid.

KEEP AN EYE OUT FOR… Never “set and forget” a spread with a short option. If you happen to get assigned on the short call and get a short stock position at the strike price, DON’T PANIC. Simply exercise your long call immediately to buy back the stock at the lower strike price.

Also, keep an eye out for underlyings that are due to pay a dividend. One of the biggest risks of short calls is dividend risk. Dividend risk is the risk that you’ll get assigned on your short call option before the dividend’s ex-date. This includes short calls that are a part of a spread. When this happens, you’ll open the ex-date with a short position and actually be responsible for paying that dividend yourself. You can avoid this by closing your spread before the end of the regular-hours trading session the night before the ex-date.

Note: The day before the ex-dividend your broker may take action in your account to close any positions that have dividend risk. It’s important to read and understand your specific broker’s options agreement to know if that is the case.

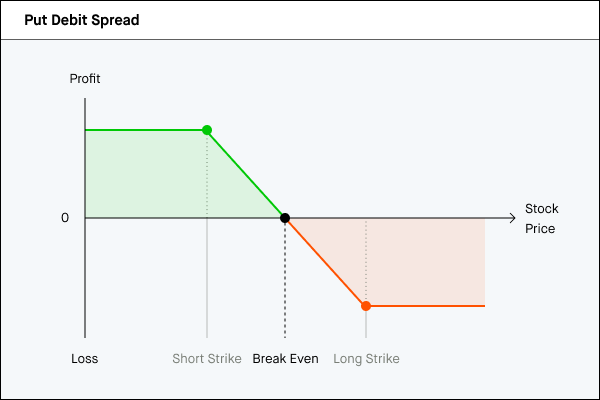

PUT DEBIT SPREAD (other names: long put spread or long put vertical)

PROFIT GRAPH:

WHY TRADE IT? You think a stock is going down imminently

OPTIMAL CONDITIONS: Low implied volatility, bearish stock, sector, and market

SETUP: Long put + short lower strike put (same expiration)

EXAMPLE: Buy August 50 Put for $5 + sell August 45 Put for $2. Net cost = $3 (x100 = $300 per spread)

COST: Cost of long put, less premium received for short put (In this example, $3)

THEORETICAL MAX PROFIT: Limited to distance between strikes minus cost of trade ($5 wide spread - $3 net cost = $2 max profit)

THEORETICAL MAX LOSS: Net cost (debit) of trade (In this example, $3)

BREAKEVEN AT EXPIRATION: There’s one breakeven point (at expiration) at the long strike less the debit paid (50 - $3 = $47 breakeven)

BEST CASE TO NAIL IT: Stock moves lower immediately, resulting in a profit. A simultaneous rise in implied volatility could help, too, but the rise in the short option would somewhat offset the rise in the long option.

WHAT CAN GO WRONG? Stock doesn’t drop quickly enough, or the stock is above breakeven as expiration nears

A drop in implied volatility and time decay could deflate the option premiums while the trade is on. However, because there is both a short option (benefitting from deflating value) and a long option (not so much), the impact overall is less than if it were just a long put position.

CLOSING THE TRADE: Just like buying single options, your goal is to buy a put debit spread and sell it for a higher price in order to profit, ideally as a package. The optimal way to do this is to simply execute the opposite transaction–sell the higher put strike and buy the lower put strike, as a package, for a credit.

If the stock goes below both strikes (this is the best-case scenario), you’ll be near max theoretical profit. Consider closing the trade before expiration to lock in profits. This could mean selling the spread at slightly less than max value in order to eliminate any upside risk before expiration.

If the position has moved against you, consider setting a price where you will sell the spread to cut your losses and close your position. If there is no bid (0 bid means no willing buyer) for the spread at expiration, simply let both legs expire worthless and they will be removed from your account after expiration. If this happens, the loss will be limited to the net debit paid.

KEEP AN EYE OUT FOR… Never “set and forget” a position with a short option. If you happen to get assigned on the short put and get a long stock position at the strike price, DON’T panic. Exercise your long put immediately to sell the stock at the higher strike price.

Credit spreads (aka short vertical spreads)

Credit spreads are usually an eye-opener for options traders, and they do take some getting used to since most new options traders are familiar with buying options or spreads. For most, selling options doesn’t enter the equation other than with covered calls or cash secured puts. So what actually is a credit spread?

Credit spreads enable traders to become “premium sellers,” which is a fancy way of saying, they collect a credit to open a position. Unlike “premium buyers” where they hope to buy low and sell high, sellers of credit spreads hope to sell high and buy low. This has a number of potential advantages, but the main one is that time is on your side when you’re a premium seller. Every day that goes by, options will lose some of their value (all other things remaining equal), which is what we call time decay. Sellers of credit spreads look to profit from this, referring to it as “collecting theta,” which is the fancy term for time decay.

Credit spreads are also directional; meaning, if you are bullish you can sell a put credit spread, and if you’re bearish you can sell a call credit spread. Why might you do this instead of buying a debit spread? Once again, this allows you to have a directional opinion on the stock while having time decay working for you.

Another reason traders sell credit spreads is to possibly take advantage of stocks exhibiting high implied volatility. Remember, when implied volatility is high, option prices are high, relatively speaking. As we mentioned in Volatility Explained, volatility is like a rubber band, and tends to revert back to its historical average. Selling credit spreads attempts to take advantage of this by selling options with relatively high prices, hoping implied volatility recedes back to normal levels.

One very important note: credits spreads are almost always done using out of the money options. If you sell a credit spread with deep in the money options, you are immediately putting yourself at risk for early-assignment on the short leg of your credit spread.

As you can see, for certain investors, selling credit spreads can pack a powerful 1-2-3 punch—they are directional, while taking advantage of time decay and high implied volatility. This is a big reason why this strategy is commonly used by professional and experienced traders alike.

Here are the details on both a call credit spread and a put credit spread.

CALL CREDIT SPREAD (other names: short call spread or short call vertical)

PROFIT GRAPH:

WHY TRADE IT? You think a stock is going down within a certain time frame

OPTIMAL CONDITIONS: Medium to high volatility, bearish stock, sector, and market

SETUP: Short call + long higher strike call in the same expiration

EXAMPLE: Sell August 50 Call for $5 + buy August 55 Call for $2. Net credit = $3 (x100 = $300 per spread)

TOTAL CREDIT: Credit of short call, less premium paid for long call (In this example, $3)

THEORETICAL MAX PROFIT: Limited to the total credit received (In this example $3 x 100; $300)

THEORETICAL MAX LOSS: Difference between the strikes minus the credit (55 - 50 = $5 -$3 credit = $2 max loss)

BREAKEVEN AT EXPIRATION: There’s one breakeven point (at expiration) at the short strike plus the credit (50 + $3 = $53 breakeven)

BEST CASE TO NAIL IT: The stock moves lower. A range-bound stock can help the trade profit, but this takes time. The stock can even go up as long as it stays below the short strike. A drop in volatility can also help.

WHAT CAN GO WRONG? A quick, and/or big move to the upside. Worst case is the stock breaks through the strike prices of both options.

A rise in implied volatility could inflate the option premiums while the trade is on. The short option can suffer from the rising price. However, since there is a long option (benefitting somewhat from inflating value), the impact overall is less than if it were just a short call position.

CLOSING THE TRADE: Ideally, the stock stays below your short call strike and both options lose their value and expire worthless. In this case, you keep the entire credit that you collected when you sold the spread, and the options are removed from your account.

If you have a profit on the trade before expiration and are worried that the stock may rebound and start moving higher, you can buy the spread back by effecting an opposite transaction–buy the lower strike call and sell the higher strike call, for a debit, as a package.

If the stock rallies and your credit spread gains in value (resulting in a loss on the trade), you can also attempt to cut your losses by buying the spread back for more than you paid. If the spread is trading at max value (the width of the strikes), you may have to place a bid slightly higher than max value to get out of the position, or allow both legs of the spread to be exercised and assigned.

KEEP AN EYE OUT FOR… Never “set and forget” a position with a short call option. You could be assigned and receive a short stock position. If you do get assigned, DON’T PANIC. Simply exercise your long call immediately to buy back and close the short stock position.

Also keep an eye out for underlyings that are due to pay a dividend. One of the biggest risks of short calls is dividend risk. Dividend risk is the risk that you’ll get assigned on your short call option before the dividend’s ex-date. This includes short calls that are a part of a spread. When this happens, you’ll open the ex-date with a short position and actually be responsible for paying that dividend yourself. You can avoid this by closing your spread before the end of the regular-hours trading session the night before the ex-date.

Note: The day before the ex-dividend your broker may take action in your account to close any positions that have dividend risk. It’s important to read and understand your specific broker’s options agreement to know if that is the case.

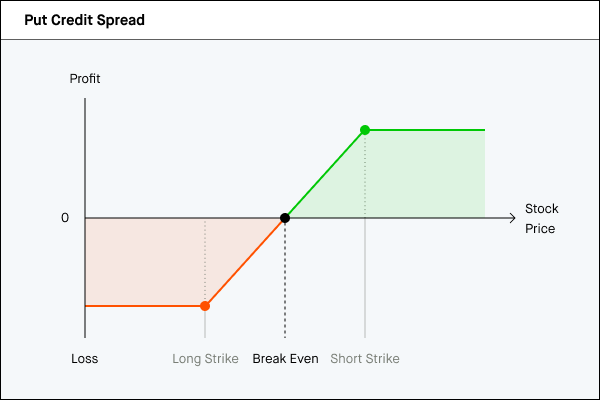

PUT CREDIT SPREAD (other names: short put spread or short put vertical)

PROFIT GRAPH:

WHY TRADE IT? You think a stock is either staying in a range or going higher within a certain time frame

OPTIMAL CONDITIONS: Medium to high volatility, bullish stock, sector, and market

SETUP: Short put + long lower strike Put in the same expiration

EXAMPLE: Sell August 50 Put for $5 + buy Aug 45 put for $2. Net credit = $3 (x100 = $300 per spread)

TOTAL CREDIT: Credit of short put, less premium paid for long put (In this example, $3)

THEORETICAL MAX PROFIT: Limited to the total credit received (In this example $3)

THEORETICAL MAX LOSS: Difference between the strikes minus the credit received (50 - 45 = $5 - $3 credit received = $2 max loss)

BREAKEVEN AT EXPIRATION: There’s one breakeven point (at expiration) at the short strike less the credit ($50 - $3 = $47 breakeven)

BEST CASE TO NAIL IT: The stock moves higher. A range bound stock can help the trade profit, but this takes time. Stock can even go down as long as it stays above the short strike. A drop in volatility can also help.

WHAT CAN GO WRONG? A quick, and/or big move to the downside. Worst case is the stock drops below the strike prices of both options.

A rise in implied volatility could inflate the option premiums while the trade is on. The short option can suffer from the rising price. However, since there is a long option (benefitting somewhat from inflating value), the impact overall is less than if it were just a short put position.

CLOSING THE TRADE: Ideally the stock stays above your short put strike and both options lose their value and expire worthless. In this case, you keep the entire credit that you collected when you sold the spread, and the options are removed from your account.

If you have a profit on the trade before expiration and are worried that the stock may begin to drop, you can buy the spread back by effecting an opposite transaction–buy the higher strike put and sell the lower strike put, for a debit, as a package.

If the stock falls and your credit spread gains in value (resulting in a loss on the trade), you can also attempt to cut your losses by buying the spread back for more than you paid. If the spread is trading at max value (the width of the strikes), you may have to place a bid slightly higher than max value to get out of the position, or allow both legs of the spread to be exercised and assigned.

KEEP AN EYE OUT FOR… Never “set and forget” a position with a short option. You could be assigned and receive a long stock position. If you do get assigned, DON’T PANIC. Simply exercise your long put immediately to sell and close the long stock position.

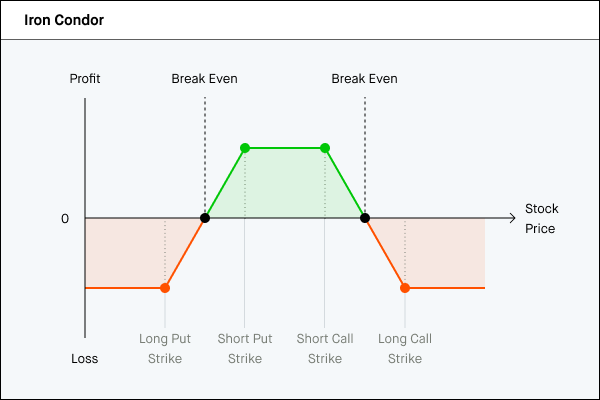

Iron condors

Despite the name seemingly straight out of a Marvel comic book, the iron condor is uniquely designed to take advantage of a sideways market, or an instance where you think the implied volatility might drop without a huge move in the stock.

It might look complicated at first, but it’s really just a combination of a call credit spread and a put credit spread (like we talked through above), where the options for both spreads are all out of the money. If the stock doesn’t move much, and all the options remain out of the money, in time, they’ll all eventually collapse in value and you’ll see a profit.

Similarly, if the volatility collapses, both short spreads will show a profit. The maximum reward is the total credit from both spreads, but the maximum risk is the width of the spread minus the total credit. Remember, the stock can only move against one of the short spreads. Let’s take a closer look below.

NAME: IRON CONDOR

PROFIT GRAPH:

WHY TRADE IT? You think a stock is going to be range bound within a certain time frame

OPTIMAL CONDITIONS: High implied volatility that falls over time combined with no movement from the stock

SETUP: Put credit spread (short put + lower long put) placed below the current stock price

Call credit spread (short Call + long higher strike call) placed above the current stock price

EXAMPLE: Sell August 55 Call for $3 + buy August 60 Call for $2. Net credit = $1 (x100 = $100 per spread)

Sell August 45 Put for $3 + buy August 40 put for $2. Net credit = $1 (x100 = $100 per spread)

Total net credit of $2 (x100 = $200 per spread)

CREDIT: Credit of both short options, less premium paid for both long options (In this example, $2)

THEORETICAL MAX PROFIT: Limited to the credit received for both the put and call spreads (In this example $1 + $1 = $2 x 100 = $200)

THEORETICAL MAX LOSS: Difference between the strikes minus the total credit received for the iron condor (5 - $2 = $3 x 100 = $300)

BREAKEVEN AT EXPIRATION: There are two breakeven points (at expiration). At the Short Call strike plus the Credit (55 + $2 = $57); and at the Short Put strike minus the Credit (45 - $2 = $43).

BEST CASE TO NAIL IT: Stock stays range bound and the implied volatility drops. Even if the IV doesn’t drop, you’ll profit from time decay if the stock doesn’t move much. As long as the stock stays in between the short strikes, you’re good.

WHAT CAN GO WRONG? A quick, and/or big move in either direction. Worst case is the stock breaks through the strike prices of both options on either side.

A rise in implied volatility could inflate the option premiums while the trade is on. The short option can suffer from the rising price. However, since there is a long option (benefitting somewhat from inflating value), the impact overall is less than if it were just a short Call and short Put position.

CLOSING THE TRADE: Just as you would close a call credit spread or put credit spread, you have a few choices depending on how the trade plays out.

Best case scenario—if the stock stays in between your short strikes by expiration, all four options will expire worthless. You’ll keep the entire credit for the iron condor, and the options will be removed from your account after expiration.

If you’re seeing a profit on the iron condor (meaning the stock has stayed range bound and time has marched closer to expiration), you can buy the entire iron condor back for a debit lower than what you sold the iron condor for. Remember, when selling spreads, you want to sell high and buy low.

If the stock moves up or down and the trade starts to go against you, you can try to buy the iron condor back for more than what you sold it for, incurring a loss. If the stock is through both legs of one of the credit spreads, you can also allow one side of the iron condor to be exercised and assigned. Meanwhile the opposite side of the trade should expire worthless. This will realize a max loss on the trade.

KEEP AN EYE OUT FOR… Never “set and forget” a position with a short option. You could be assigned and receive a stock position. If you do get assigned, DON’T PANIC. Simply exercise your long option immediately to close out the stock position. For example, if you get assigned on the short put, exercise the long put. And vice versa with the calls.

And don’t forget dividend risk. This includes short calls that are a part of an iron condor. When this happens, you’ll open the ex-date with a short position and actually be responsible for paying that dividend yourself. You can avoid this by closing at a minimum your call credit spread before the end of the regular-hours trading session the night before the ex-date.

Note: The day before the ex-dividend your broker may take action in your account to close any positions that have dividend risk. It’s important to read and understand your specific broker’s options agreement to know if that is the case.

One more thing…

With all debit and credit spreads (aka vertical spreads), there is always the risk that the stock closes between your strikes at expiration. This can introduce brand new risk into the picture. Specifically, one leg of your spread can either be exercised or assigned, while the other leg of the spread goes out worthless leaving you with long or short stock. If this happens, the theoretical max gain and loss no longer applies and your risk is now that of long or short stock.

How can you try to avoid this? The easiest and best way to avoid this scenario is to manage your positions diligently and avoid holding positions into expiration whenever possible. Strange things can happen on the close of expiration and positions you thought were out of the money might swing into the money and vice versa. Once again, options are not a “set and forget” product.

Final thoughts

We’ve covered a lot here! Take a breath, and remember, Rome wasn’t built in a day—neither is a good options trader. It takes time, practice, and experience to fully grasp these strategies. But as you build your experience with options, it’ll add brand new tools to your toolbelt and give you different ways to trade price, time, and implied volatility. Remember, these are the building blocks that nearly all other options strategies are built on, so it makes sense that you’ll spend a lot of time learning them.

Take it from Yoda—Patience you must have.

Next up: Consider your options

Disclosures

Any hypothetical examples are provided for illustrative purposes only. Actual results will vary.

Content is provided for informational purposes only, does not constitute tax or investment advice, and is not a recommendation for any security or trading strategy. All investments involve risk, including the possible loss of capital. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Options trading entails significant risk and is not appropriate for all customers. Customers must read and understand the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before engaging in any options trading strategies. Options transactions are often complex and may involve the potential of losing the entire investment in a relatively short period of time. Certain complex options strategies carry additional risk, including the potential for losses that may exceed the original investment amount. Complex options strategies can entail more significant transaction costs and commissions which may impact potential returns. You should familiarize yourself with your broker's commission and fee schedules prior to placing any trades.

Robinhood Financial does not guarantee favorable investment outcomes. The past performance of a security or financial product does not guarantee future results or returns. Customers should consider their investment objectives and risks carefully before investing in options. Because of the importance of tax considerations to all options transactions, the customer considering options should consult their tax advisor as to how taxes affect the outcome of each options strategy. Supporting documentation for any claims, if applicable, will be furnished upon request.

New customers need to sign up, get approved, and link their bank account. The cash value of the stock rewards may not be withdrawn for 30 days after the reward is claimed. Stock rewards not claimed within 60 days may expire. See full terms and conditions at rbnhd.co/freestock. Securities trading is offered through Robinhood Financial LLC. Futures trading offered through Robinhood Derivatives, LLC.